VPN hacked and lateral movements

The scan had been running for several minutes, and the attacker’s screen displayed a list of listening applications detected on the network. He had entered the post-exploitation phase, meaning he had successfully infiltrated the system and was now trying to extend his control to other devices.

His goal was to escalate privileges: using the access he had obtained to compromise a machine with higher-level permissions. This pivot would allow him to retrieve sensitive information, cause a service disruption, or deploy ransomware.

It only took a few minutes. Like many corporate networks, the security efforts were focused on the perimeter of the information system to prevent external threats from getting in.

But that wasn’t enough, and now that the hacker was inside, it became much easier for him to continue toward his final goal.

VPN account compromise

The company had implemented a classic network security strategy by reducing the exposure of its applications to the internet while still meeting the needs of remote users to access business services. To do this, the company followed this approach:

-

Redefined its network architecture, which was initially "flat" with no segmentation. Business applications were placed in VLANs based on their criticality, and direct internet exposure was cut off by implementing firewall rules.

-

Implemented a VPN with multi-factor authentication (MFA). Each off-site user connected remotely via an SSL VPN connection, using a username/password pair and MFA verification. The VPN was configured on each user’s workstation, and after authentication, the user was assigned a local IP address associated with the virtual interface.

From a network perspective, once authenticated, the user was treated as if they were physically on-site, with the same access rights.

The strength of this approach lay in its simplicity, significantly reducing risks without too much effort. However, the weakness was in the level of trust assigned. Remote users were considered equal to those on-site, with no distinction.

The absence of strong certificate-based authentication also played a major role in the incident.

Some time before this setup, the database of a well-known social network had been compromised and published online. In addition to names, addresses, and phone numbers, hashed passwords were also revealed.

The attacker performed a rainbow table attack to recover the plaintext of a large number of these passwords. Among the victims was an employee of the company. Two password hygiene rules had not been followed: firstly, the password did not adhere to a strict security policy, and secondly, it had been reused on another service – the company’s VPN.

Profiling the target was then easy: even though the email address used was personal, it was simple to guess the professional equivalent. Like most companies, the format was “first.last@company-domain.com.”

With the email address found and the password known, the only remaining hurdle was bypassing multi-factor authentication. The attacker used the stolen database again, but this time social engineering was key. Initially, a direct phone call to the victim involved impersonating a representative from a third-party company, using manipulation to try to obtain the authentication information displayed on the smartphone screen – but to no avail.

The hacker then switched strategies, targeting the telecom provider and executing a SIM-swapping attack. By reassigning the user’s phone number to a device under his control, he could then enter the one-time MFA code.

Once inside the network, the local scan could begin. The lateral move only took an hour to complete.

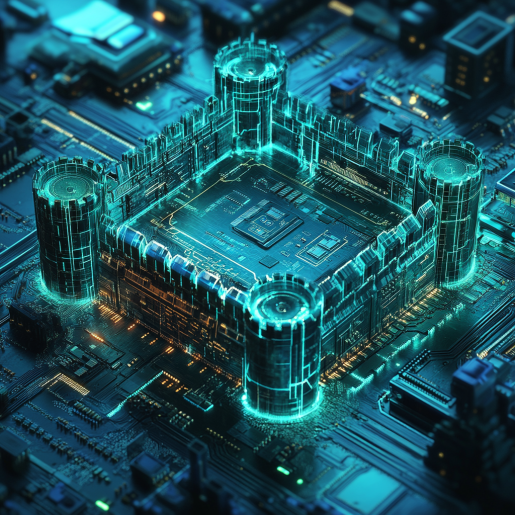

Micro-segmentation and Zero Trust

The main issue with using “coarse-grained” segmentation alongside VPN implementation lies in the trust level assigned to the user. In the article The Information System was already compromised the attacker was already inside the network, bypassing the earlier stages of the attack. The threat was internal. In the scenario described here, the focus was primarily on the VPN authentication’s ability to withstand the attack. But once inside the network, it’s too late.

An interesting strategy to combat this type of attack is to redefine segmentation and trust principles:

-

On one hand, through the implementation of micro-segmentation, denying users access to an entire network or VLAN, even if authenticated. The idea is to provide application-specific access and inherently prevent network-layer attacks at OSI Layer 3. By relying exclusively on Layer 7, as the ZTNA (Zero Trust Network Access) model suggests, it becomes much harder for the attacker to discover vulnerable applications and carry out lateral movements.

-

On the other hand, applying the principle of least privilege: an authenticated user only has access to the applications they need, and nothing more. The combination of granular access and least privilege significantly reduces the risk of lateral movement.

Zero Trust Network Access

These two characteristics are integral parts of the Zero Trust Network Access principle.

In addition, some ZTNA architectures offer the feature of removing exposure, preventing attackers from detecting and interacting directly with the VPN gateway.

More broadly, ZTNA allows for a technical redefinition of the perimeter concept and, on a higher level, a rethinking of the principle of trust.

If you’d like to learn more about Zero Trust, stay tuned for upcoming articles: